A dugout canoe in the Museum’s artifact collection has a story to tell, but which story is up for debate.

From L to R: Gwendolyn Waldorf, Steve Stoutamire, Charlottee Stoutamire, Ric Stoutamire, and Julie Duggins

Steve Stoutamire visited the Museum in December with his mother, and again in January, 2018, with his cousin Ric. They believe that the canoe, displayed outside the Phipps gallery, came from their family. Steve’s great-grandfather, J.D. Stoutamire, found a canoe on a sandbar in the Ochlocknee River. High water had washed away the sand to expose it. He kept the canoe in his yard for years and then, between 1943 and 1952, donated it to the “the museum in Tallahassee”. The Tallahassee Museum opened years later, in 1958, leaving the canoe’s presence at the Museum a mystery.

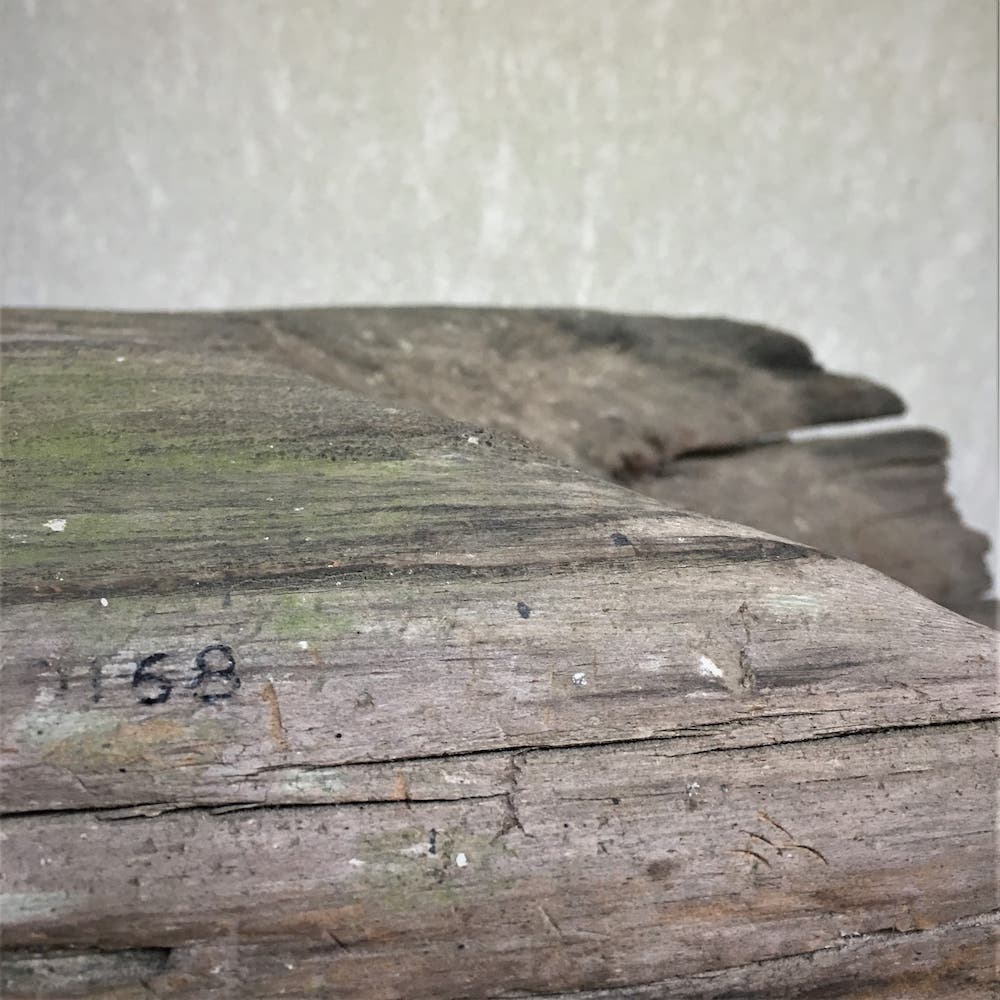

A catalog number on the canoe connects it to a second story, and another family. When the staff first recorded the canoe, in 1979, they thought the canoe had come to the Museum from the FSU Anthropology department, and may have come from a pond in Thomas County, Georgia. Recent information from that family, the Tomlinsons, indicates that their canoe surfaced in the mid-1950s and was donated to a museum in Tallahassee.

Julie Duggins and Steve Karacic of the Department of State’s Bureau of Archaeological Research visited the Museum in March to document the canoe. The Stoutamire family offered to pay for radiocarbon dating, so the archaeologists took a wood sample and learned that the canoe dates between AD 1500 and AD 1600. They also measured the canoe, sketched it, and checked for evidence of pigment using portable X-Ray Fluorescence. This dugout is reportedly either from the Ochlockonee River or a lake near the Georgia-Florida line, both of which are uncommon locations to find a dugout. Of the over 400 canoes in the state database, only a handful are from the panhandle.

“Florida has the largest concentration of dugout canoes in the world, but each canoe is important because it adds to our understanding of how Florida’s early peoples lived,” said Duggins. “This particular canoe is unique because we do not have many documented canoes from the Panhandle area.”

The Museum and the Stoutamires continue to research not only the canoe, but also museums that existed in Tallahassee during the 1940s and early 1950s. The family is checking photographs and a home video, hoping to find an image of their canoe while on family property. But for now, the dugout’s origins remain a mystery.

“We have two competing origin stories about canoes that might be ours,” said Assistant Curator, Gwendolyn Waldorf. “In both cases they were donated to a museum in Tallahassee before we existed. We don’t yet know which canoe we have, or if ours is a third one.”